- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Amid growing IPO rumblings, Big Hit shifts away from heavy reliance on BTS

K-pop mega group BTS are undoubtedly a huge financial blessing for their record label-management agency Big Hit Entertainment. Thanks to the septet’s smash hit album “Map Of The Soul: Persona” and sellout concerts worldwide, Big Hit posted record sales of 587.2 billion won (US$472.2 million) in fiscal year 2019, with net earnings soaring to 72.4 billion won.

At the same time, it could be argued that Big Hit’s heavy reliance on BTS poses a risk for the company as well. It presents a fundamental and structural hurdle that the company must address to grow bigger and remain strong going forward — to prove that its achievement isn’t just tied to the success of a single artist or a franchise.

Clearly aware of this situation, the company, founded by producer Bang Si-hyuk, nicknamed Hitman, in 2005, has been on course to methodically reduce such risk by acquiring smaller-but-strong talent agencies, investing in and developing new projects, and expanding into non-music businesses.

The latest in Big Hit’s portfolio diversification is the acquisition of Pledis Entertainment, a midsized talent agency that manages popular boy bands NU’EST and Seventeen. Pledis, established in 2007 by Han Sung-soo, who worked as a manager of singer BoA of SM Entertainment, is a seasoned entertainment company, responsible for popular artists, such as After School and Son Dam-bi.

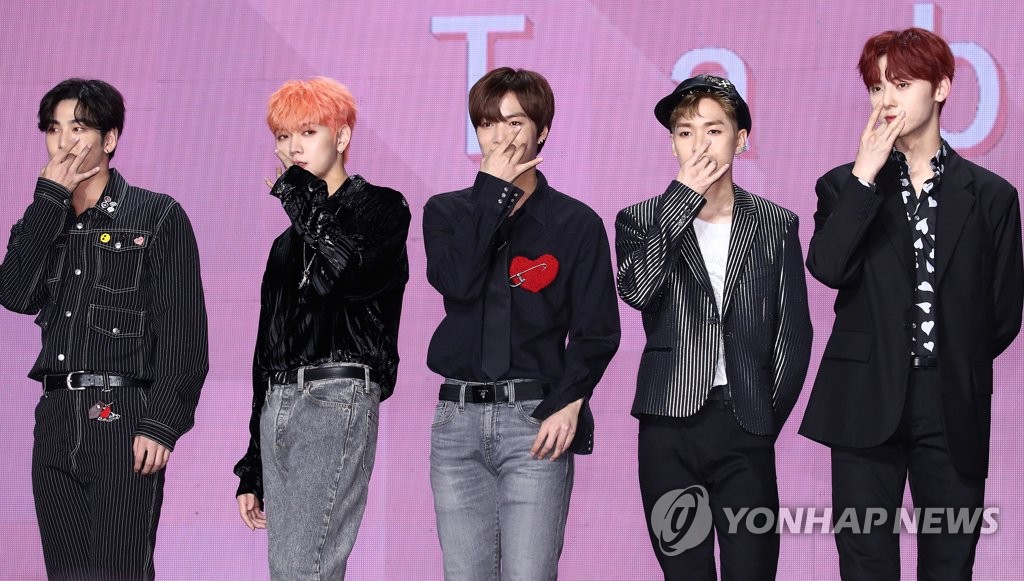

This file photo from Oct. 21, 2019, shows South Korean boy group NU’EST posing for photos during a showcase for the group’s seventh EP “The Table” in Seoul. (Yonhap)

The deal announced Monday has been an open secret within the industry for some time, with several media reports having been made since January. Big Hit had rebuked the reports with typical “nothing to confirm” statements.

The reports and the eventual confirmation Monday have fueled prospects that Big Hit may go public in 2020, by holding an initial public offering (IPO) later this year. It’s been reported that the company has chosen several brokerages, including NH Investment Securities, Korea Investment Securities and JP Morgan, to handle its IPO.

Big Hit’s current valuation among brokerages is estimated from 2 to 4 trillion won.

“Big Hit’s reliance of over 90 percent (in income) on BTS could drop immediately down to 75 percent from the acquisition of Pledis,” Kim Hyun-yong, an analyst at eBEST Investment & Securities, said in a recent outlook report on the K-pop agency.

Kim projected that operating profit figures for Big Hit following the Pledis acquisition could increase to as high as 120 billion won annually. Operating profit for Big Hit stood at 98.7 billion won last year.

The Pledis deal marks Big Hit’s second corporate acquisition, preceded by the buyout of Source Music, home to popular girl band GFriend in July of last year.

Through collaboration with Source Music, Bit Hit, currently without a girl group in its in-house lineup, plans to launch an all-female act in 2021 through a global audition project.

Internally, Big Hit has developed and debuted Tomorrow X Together, a five-member boy band, last year in hopes of creating the next global K-pop sensation. So far, the group has proved to create a strong buzz, collecting 10 rookie-of-the-year awards during last year’s music awards season and making their American television debut last week following the release of their new EP, “The Dream Chapter: Eternity.”

Big Hit has been making substantial commitments in non-music businesses as well.

In March of last year, the company established a 7 billion-won joint venture, Belift Lab, with South Korean entertainment giant CJ ENM to nurture new idol groups. Belift Lab’s first project will be a K-pop audition TV show, named “I-Land,” scheduled to be aired on Mnet next month.

BTS has also ventured into the realm of gaming. Last year, Netmarble Games, a South Korean mobile game developer and publisher, released “BTS World,” a simulation game built around the idea of developing BTS members into global superstars for mobile devices.

Big Hit is apparently gearing up to develop its own games, acquiring game studio Superb last year, which has developed music games since 2016.

The company’s long-term goal in spreading out the business portfolio is crucial as BTS members are eventually bound to enter hiatuses to fulfill their two-year military duties, posing a risk in terms of Big Hit’s corporate stability.

All able-bodied South Korean young men are required to serve in the military, as the Korean Peninsula still remains technically at war since the 1950-53 Korean War ended in a ceasefire, not a peace treaty.

In terms of more broader corporate goals, Big Hit announced in February that it is working to establish an industrywide business standard that epitomizes and encapsulates the success the company has seen though BTS and apply it in other projects.

This idea is comparable to Culture Technology, a concept created by SM Entertainment founder Lee Soo-man, which lays down detailed steps for popularizing K-pop in the global market. Lee has been pitching CT as an entertainment industry standard that can be used in different regions of the world to create new versions of “hallyu,” a term referring to the popularity of Korean culture.

“It appears Big Hit is becoming more serious in terms of its business, trying to make a big, bold statement,” said Lim Jin-mo, music industry critic. “Big Hit’s embrace of bands, such as NU’EST and Seventeen, signals serious business.”

Lim also pointed out risks that follow rapid business expansions, such as potential liquidity crunches, and a decrease in support and resources toward the artists.

“There’s always the possibility that the expansions could backfire,” Lim said. “Almost all agencies tend to have one strong act accompanied by smaller ones. Allocating resources to various teams could potentially end up diluting corporate energy toward artists.”