- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Reckoning with cultural diversity imperative in K-pop moving beyond : observers

In the past several weeks, global fans of K-pop came under a sudden burst of collective observation by the international media, with a wave of positive coverage depicting K-pop fans as agents of change amid a series of high-profile cases of political activism related to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement in the United States.

While the general validation of K-pop fans as enablers of social justice was, for the most part, received as a cause for celebration within the fan community at large, the K-pop industry itself hasn’t exactly had a sterling track record when it comes to proper recognition of cultural diversity and representation.

It continues to struggle with issues of racial stereotypes and cultural misappropriations to this day.

Case in point: the highly popular music video for “How You Like That” by BLACKPINK, one of the biggest K-pop girl groups today, came under scrutiny by Indian fans for using a small statue of the elephant-headed Hindu deity Lord Ganesha as a prop.

The statue appeared for a split second on the floor in a scene where member Lisa sings seated on a large arm chair. Indian viewers were quick to point out that not only was it offensive to use the Lord Ganesh statue as a prop but placing it on the floor next to a person’s feet was seen as disrespectful.

“Ok. This is really making me angry. But how can you use my culture as one of your damn aesthetics. We Hindus do not deserve this disrespect,” Twitter user @Got7_Jolly wrote Saturday, a day after the video was released on YouTube.

YG Entertainment, BLACKPINK’s management agency, on Tuesday uploaded a new edit of the video, this time with the deity statue cropped out. The company did not issue a statement on the re-upload.

K-pop group IZ*ONE also faced a controversy last month, when it released a teaser for the “Secret Story of the Swan” music video. In the teaser, group leader Eunbi appeared wearing a gem on her forehead, with some international fans alleging it was an ill-conceived misappropriation of a bindi from Hindu culture.

In an apparent acknowledgement of the online hoopla, the gem was edited out from the final music video, which ended up being released a day later from its originally announced date of June 15.

The BLACKPINK and IZ*ONE incidents may be seen as relatively light-hearted compared to more blatant mishaps from K-pop stars in the past.

In 2017, Mamamoo faced strong online backlash after putting on dark makeup while covering Bruno Mars’ “Uptown Funk” during the group’s concert, upsetting black fans. The quartet later issued an apology, saying, “We were extremely ignorant of blackface and did not understand the implications of our actions.”

Red Velvet singer Wendy also took heat from international black fans in 2018 when doing an exaggerated impression of how black women in America spoke on South Korean television.

Momoland, which recently signed with ICM Partners to broaden its presence abroad, also came under fire for the 2018 music video of “Baam,” which was filled with scenes depicting various cultures in stereotypes.

Researchers of Korean pop culture denote the fine but distinct line between cultural appropriation and appreciation, and how important it is to distinguish one from the other.

“Appropriation borrows from another culture in order to elevate the person who takes; appreciation borrows from another culture with permission in order to elevate the culture and people from whom they’re borrowing,” David Oh, an associate professor of communication arts at Ramapo College in New Jersey, told Yonhap News Agency in a recent email interview.

Oh added, “Appropriation might even mock the people they’re taking from with racial caricatures and stereotypes. This is never right.”

In today’s climate of ever-growing demands for political correctness, it is imperative that the K-pop industry increase its recognition of diversity and appreciation of different cultures, Oh argues.

“If K-pop wants to cultivate its relationship to its fans, then it needs to have a matching progressive vision. If Korea wants to continue to gain worldwide esteem and soft power, then it can do this, in part, by differentiating itself as a progressive leader in the world.”

CedarBough Saeji, a visiting assistant professor of Korean Culture at Indiana University, predicted that future race-related missteps within the industry would end up having a bigger negative impact than ever before.

“Although diehard fans may continue to excuse anything an idol does, entertainment companies and the idols themselves should be aware that race-related missteps such as those seen in the past will have a larger negative reaction than ever before,” Saeiji predicted.

Unlike K-pop super fans at home and overseas, who often organize group charity events in the name of idols and projects to raise awareness on social issues, K-pop artists and the industry, along with the broader Korean entertainment scene at large, have traditionally kept politics at arm’s length.

Voicing convictions and taking political stands have often led to stars being stigmatized and sidelined from major projects, as seen in the “blacklist” scandal in which the previous conservative government drafted a secret list of artists critical of the administration to disadvantage them in various ways.

But through the course of BLM in the U.S., some K-pop companies have entered what some may consider as an awakening phase — officially recognizing and addressing for the first time non-music and non-entertainment issues that politically and philosophically affect fans of K-pop.

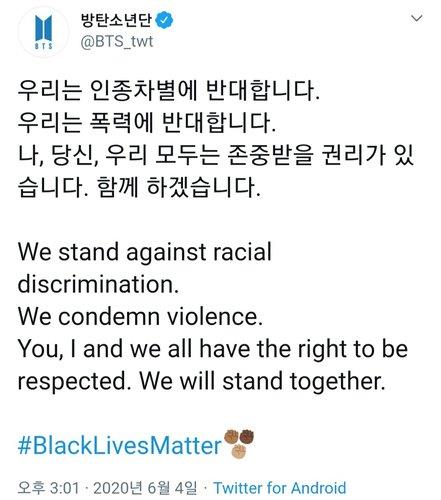

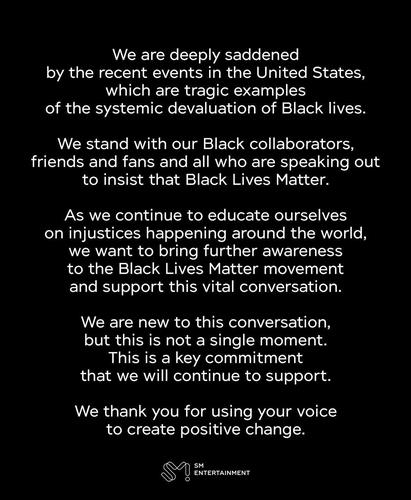

Mega K-pop group BTS and its management agency Big Hit Entertainment took a public stand, showing support toward the BLM civil rights movement and donating US$1 million to the cause. SM Entertainment, arguably the most consequential company in laying the foundation for today’s K-pop, also released a public statement on BLM last month.

“We stand with our Black collaborators, friends and fans and all who are speaking out to insist that Black Lives Matter,” SM, the company behind EXO, NCT 127, TVXQ, SHINee and Red Velvet, said in an English-language statement on June 19.

American pop singer Alexandra Reid, a former member of K-pop girl group BP Rania, said that K-pop companies would benefit from having designated cultural liaisons to educate artists and creative teams within agencies.

“From living over there, I see how a lot of it isn’t malicious, and they truly don’t know better. Korea is so homogenous that they aren’t exposed to other races and a lot of times they have sadly only been exposed to the stereotypes of black people,” Reid told Yonhap News Agency in an email interview.

Reid was the first-ever African American female K-pop idol active in Korea for almost two years from November 2015.

As a black artist who worked in an industry predominantly homogeneous, Reid recalled experiencing racism in the South Korean entertainment scene and music fans.

“There were racial slurs thrown at me, comments that I just didn’t look right on a K-pop stage and would never fit in and even that I was ruining K-pop.”

Despite some of her negative experiences in South Korea, Reid still sees K-pop as “truly the ultimate pop.”

“If I can open that door for all shades and colors, then that’s the greatest accomplishment I could ever hope for,” said Reid.

Some international K-pop fans of color also ask that Korean entertainment companies implement corporate policies to better educate artists on cultural issues that are sensitive.

“Hire experts to teach regular cultural sensitivity classes, get a second or third opinion before putting questionable content out into the world,” said Twitter user @DavonnaDarling, an African American fan of SM based in Atlanta, who organized the #SMBLACKOUT movement on Twitter.

Chermel Porter, an African-American freelance music writer and a K-pop follower based in New Jersey, shared a similar viewpoint.

“K-pop agencies should enlist the idea of ‘cultural sensitivity training’ amongst their employees and artists. By doing this I mean, agencies should scout out the help of U.S. (and other counties) social justice leaders to teach a course on the basics of insensitive racial actions,” she said.