- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

After summit, simple cold noodles from Pyongyang warm S. Koreans toward North

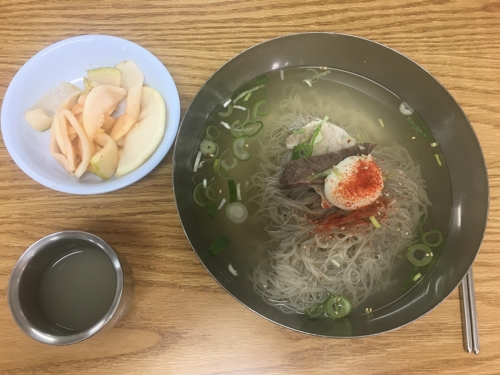

This photo shows a bowl of Pyongyang naengmyeon served in Eulji Myeonok. (Yonhap)

SEOUL, May 9 (Yonhap) — Located in a back alley of a bustling old district of hardware stores in central Seoul, the Eulji Myeonok noodle house has no proper business signboards to lure customers; all it has is the restaurant’s name painted above the doorway in out-of-fashion calligraphy.

The dish is finding new popularity following April’s inter-Korean summit, and a long queue was quickly forming outside of the two-story restaurant at lunchtime of a weekday holiday in early May even though the busy Eulji-ro commercial area was largely empty.

“I come to this place as often as time allows to have the genuine taste of ‘naengmyeon’,” said a 61-year-old man who was seen into the restaurant with his wife and daughter after waiting outside.

The wife described him as “an expert of Pyongyang naengmyeon,” a regional variety of the Korean cold noodle, from North Korea’s capital city, for which the decades-old restaurant is known.

“This is how real naengmyeon should be. My father and father-in-law, who both came from Pyongyang, also approved of it as genuinely Pyongyang style,” the man said, preferring not to be identified.

“I first came here about 40 years ago with my parents who wanted the feel of their hometown in North Korea,” he said, recalling his North Korean-born parents who weren’t able to go home after the 1950-53 Korean War divided what was previously one nation.

As his fellow Pyongyang naengmyeon lovers do, sometimes with slight variations, he counted Eulji Myeonok and three other noodle houses — two in the same area in central Seoul and the other in the border city of Uijeongbu near North Korea — as the top places that best preserve the originality of naengmyeon, whose origins are arguably as a summertime delicacy popularly eaten in northern Korea since the last Korean kingdom of Joseon.

Eulji Myeonok is run by a daughter of a North Korean refugee who fled to the southern side during the civil war and opened a restaurant, selling her hometown dish of thin buckwheat-starch noodle in cold beef broth, topped with simple pickled white radish plus thin slices of beef.

“The key selling point of Pyongyang naengmyeon is its simplicity. To some people, it could come as bland, but it has its own depth of flavor,” he noted as he was waiting for a bowl. “I can never get used to other regional versions of naengmyeon,” he added, referring to more strongly spiced noodle dishes widely eaten in the South.

For Pyongyang naengmyeon beginners like 39-year-old office worker Lee Ji-young, however, it was not the taste, but a measure of curiosity that triggered a trip to Pyongyang naengmyeon houses, a phenomenon following the successful event of the summit meeting between President Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un on April 27.

Bowls of naengmyeon brought from Pyongyang’s Okryugwan restaurant, called by its followers as “holy ground,” for the summit’s banquet session were a major source for ice-breaking jokes between the two leaders gathered for a rare chance to discuss the denuclearization of North Korea.

“I would like President (Moon) to relax and enjoy Pyongyang naengmyeon brought from afar,” Kim was televised live as telling Moon during their meet-and-greet session. Kim then said “Oops, I shouldn’t have said ‘from afar,’” making eye contact with his younger sister next to him.

It was one of the first-ever moments Kim interacted with the South Korean media and he succeeded in making it a chance to revamp his image as a warmonger who conducted four nuclear weapons tests and dozens of missile launches so far during his seven-year reign.

With the so-called noodle diplomacy, major Pyongyang naengmyeon restaurants across the South were inundated with waves of South Koreans wanting to experience the North Korean delicacy at the date of the summit.

President Moon Jae-in (R) and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un eat Pyongyang naengmyeon during their summit dinner on April 27, 2018. (Yonhap)

Nearly two weeks after the summit, the popularity is still growing.

“At the date of the summit, nearly 30 percent more customers than the average came to have a taste of our naengmyeon,” a staff worker at Eulji Myeonok said. “Even after the summit, 10 or 20 percent more dinners continue to visit,” she noted.

In the wake of the interest, about 20 online petitions have been filed with the presidential office Cheong Wa Dae, calling for an opening of a South Korean branch of the North Korean Okryugwan restaurant.

Cheong Wa Dae did not officially review the petitions because they have not garnered the 200,000 online votes that require the presidential office to issue an official response — one of Moon’s signature policies to reach out to the public.

But it did respond to the calls last Friday by serving the Cheong Wa Dae version of the famous North Korean noodle at its cafeteria for lunch.

Amid the heated popularity in the South and possibly in homage to the recent inter-Korean summit, the North’s mouthpiece news wire, Korean Central News Agency, ran a short article featuring the cold noodle.

“Pyongyang has boasted of many special dishes from long ago … Among them are Pyongyang cold noodle,” to the news article published three days after the summit. “In particular, Pyongyang cold noodle is very popular for its fresh flavor and fragrance not only in summer but also in winter,” it said.