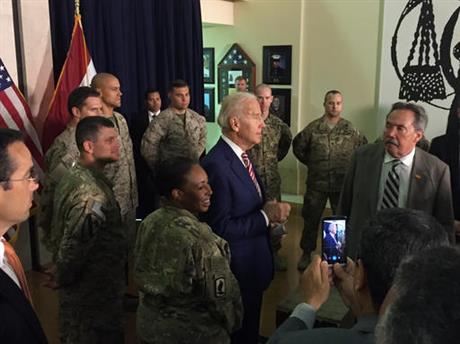

Vice President Joe Biden meets with U.S. diplomatic and military personnel serving in Iraq, Thursday, April 28, 2016, at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad.

BAGHDAD (AP) — Vice President Joe Biden, visiting Iraq on Thursday, described progress toward defeating the Islamic State group as “serious” and “committed” despite a crippling political crisis that threatens those gains.

Biden met separately with Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi and Parliament Speaker Salim al-Jabouri. He told reporters that he and the speaker would discuss progress against Daesh, an Arabic acronym for IS.

“It’s real. It’s serious. And it’s committed,” Biden said before his private talks with al-Jabouri.

Biden said he and al-Abadi discussed “plans in store for Mosul and coordination going on with all of our friends here. I’m very optimistic.” He added that the leaders were “working very, very hard” to put together a new Cabinet.

Biden is on his first trip to Iraq since 2011. He arrived in the capital of Baghdad after a secret, overnight flight from Washington on a military plane. He was greeted on the blistering hot tarmac by the U.S. ambassador and Lt. Gen. Sean McFarland, the U.S. commander heading the fight against IS.

His first stop was to meet with al-Abadi at the late Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s grandiose Republican Palace, which served as U.S. headquarters in Baghdad after the U.S.-led 2003 invasion. They spoke in English as reporters were allowed in briefly for the start of the meeting.

The White House didn’t disclose the rest of Biden’s itinerary, but said he would meet with other Iraqi leaders to stress national unity and discuss the campaign against IS extremists. Biden also met with U.S. personnel in Iraq.

The visit comes amid a wave of protests and demands for sweeping political reforms that have paralyzed a government already struggling with a dire economic crisis and IS. The Obama administration has stepped up its military role with more troops and equipment in hopes of putting Iraq on a better path as President Barack Obama prepares to leave office in January.

Though there’s been progress in wresting back territory from IS and weakening its leadership, senior U.S. officials traveling with Biden said any lost momentum will likely be due to political unrest rather than military shortcomings. Chaotic politics aren’t new in Iraq, but the present infighting risks becoming a distraction, with politicians more focused on keeping their jobs than fighting IS, said the officials, who weren’t authorized to comment publicly and requested anonymity.

Biden’s trip was not announced in advance, due to security concerns. Journalists accompanying him on the 17-hour journey agreed to keep it secret until he was inside Iraq.

The turmoil engulfing Iraq’s government grew out of weeks of rallies by followers of influential Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr demanding an end to pervasive corruption and mismanagement. Thousands have protested just outside Baghdad’s heavily guarded Green Zone, calling for politicians to be replaced by independent technocrats and for Iraq’s powerful Shiite militias to be brought into key ministries.

At the center of the crisis is al-Abadi, a Shiite whom the U.S. considers a welcome improvement over his predecessor, Nouri al-Maliki. Yet al-Abadi’s failures to deliver on long-promised reforms and manage Iraq’s growing sectarian tensions have threatened his ability to lead the country.

Al-Abadi is caught between ordinary Iraqis pleading for government accountability and entrenched political blocks that are reluctant to give up a powerful patronage system widely blamed for squandering Iraq’s oil fortunes. On Tuesday, Iraq’s parliament approved a half dozen new Cabinet ministers al-Abadi nominated in a gesture to protesters, but the rest of the Cabinet lineup remains in contention.

The turbulence has roiled the Iraqi capital. Last month, al-Abadi pulled troops fighting IS on the front lines to protect Baghdad amid the protests. An economic crisis spurred by collapsing oil prices has further compounded Iraq’s troubles.

Obama said in Saudi Arabia last week that al-Abadi had been a “good partner” but expressed concern about his hold on power. Obama said it was critical that Iraq’s government stabilize and competing factions unite so it can fight terrorism and right its economy.

“Now is not the time for government gridlock or bickering,” Obama said.

It was because of that bickering that Obama emerged from a meeting with Gulf leaders without the promises of financial support for Iraq’s reconstruction that he had sought. Gulf countries preferred to wait and see whether Iraq could get its political act together before agreeing to help.

Aiming to build on recent progress in retaking territory from IS, the U.S. this month agreed to deploy more than 200 additional troops to Iraq, bringing the authorized total to just over 4,000, and to send Apache helicopters into the fight. Although the White House has ruled out a ground combat role, Obama’s decision puts American forces closer to the front lines to train and support Iraqi forces preparing to try to take back Mosul.

U.S. officials would not put a timeline on reclaiming Mosul but said they expect progress to slow during the summer.

For Biden and Obama, the next nine months represent their final opportunity to position Iraq for a peaceful future before their terms end. Though they came into office pledging to end the war and did so in 2011, U.S. troops returned to Iraq in 2014 amid the rise of IS. Obama now acknowledges that his goal of defeating the militants won’t be realized during his presidency.