- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

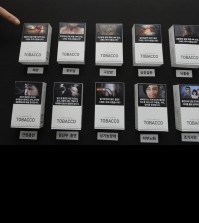

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

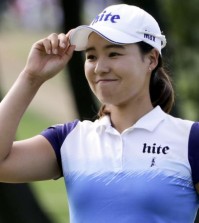

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Big league or not, youngsters say playing in US well worth trouble

By Yoo Jee-ho

SEOUL (Yonhap) — Nam Tae-hyeok went from a highly-touted high school slugger in South Korea in 2009 to a virtual unknown toiling in the U.S. minor leagues in 2012. After signing with the Los Angeles Dodgers out of high school in 2009, Nam played Rookie ball for four seasons, tallying nine home runs and 52 RBIs in 111 games.

Nam Tae-hyeok, who once played minor league baseball in the Los Angeles Dodgers’ system, speaks to reporters after getting selected by the KT Wiz in the Korea Baseball Organization in the annual draft in Seoul on Aug. 24, 2015. (Yonhap)

Nam made a not-so-triumphant return home in 2013. Two years later, on last Monday to be exact, the hulking, 187-centimeter and 95-kilogram infielder got his second baseball life, as the KT Wiz in the Korea Baseball Organization (KBO) made him the first overall pick in the non-territorial KBO draft.

Some may say Nam, now 24, wasted his crucial developmental years in his late teens and early 20s in the United States, when he could have been making progress at home. Nam said, however, he wouldn’t change a thing about his past.

“If I could turn back the time, I would still go to the United States,” he said after the draft. “I didn’t realize my dream (of playing in the majors), but it was a good learning experience. I’ve come a long way and I will do the best I can in the pro league here.”

Nam was one of four ex-U.S. minor leaguers who were selected by KBO clubs on Monday, joined by outfielder Kim Dong-yub, formerly of the Chicago Cubs system; right-hander Jung Su-min, who also played in the Cubs’ minor leagues; and outfielder Na Kyung-min, who played in the Cubs’ and later in the San Diego Padres’ minors.

Last year, there were three such players in the draft.

They all signed six-figure deals with big league clubs out of high school — more than what they would have commanded from domestic clubs had they stayed home — around 2008 and 2009, when one team after another snatched South Korean prospects. They joined the minor leagues and tried to make it to the ultimate stage, Major League Baseball (MLB).

None of the seven players drafted in the past two years reached the majors. Of this year’s class, only Na went as high as Triple-A.

Over the past several years, it’s been a disconcerting trend in South Korean baseball. Talented young players, mostly high school graduates, would join the U.S. minor leagues, and many would come home battered — physically and psychologically — and unable to play pro ball for two years.

Concerned with the exodus of young talent, the KBO, in a preemptive strike, instituted in 1998 a two-year moratorium on playing in South Korea for the likes of Nam. If a player made his professional debut outside South Korea after January 1999 but returned home hoping to compete in the KBO, he would have to sit out for two years before gaining eligibility.

Among the high school stars who signed around the same time, Lee Hak-ju, a shortstop in the Tampa Bay Rays’ Triple-A affiliate, appears to have the best shot at reaching the majors. Another former Cubs minor leaguer, right-hander Rhee Dae-eun, has taken an unusual route and is now pitching for the Chiba Lotte Marines in Japan’s Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB).

With no high school graduates having made it to the big leagues in recent years, baseball officials here say the teenagers shouldn’t sign with MLB teams out of high school, and should instead bide their time playing pro ball in South Korea before considering a move overseas.

They point to two of the three current South Korean major leaguers, left-hander Ryu Hyun-jin of the Los Angeles Dodgers and infielder Kang Jung-ho of the Pittsburgh Pirates, as prime examples.

Both Ryu and Kang played several years in the KBO and signed with their respective clubs after getting posted as free agents. Both are 28, mature enough as human beings and baseball players to hit the ground running in the majors, while still in their athletic primes.

On the flip side, Nam said he saw plenty of value in playing in the minors at a young age, and not all is lost even when players have to return to South Korea.

“I think I learned how to take care of myself and push myself in the minors,” Nam said. “In the United States, if you sit around doing nothing, no one’s going to pick you up and help. So I also learned how to approach people and be more proactive in interactions with others. If younger players today are thinking of going to the U.S. in the future, I would highly recommend it.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by many of Nam’s contemporaries, and also by Choi Eun-chul, a former minor league pitcher for the Baltimore Orioles. Choi agreed that young players can learn a great deal when they play in the minors.

“We should be more open-minded about young players going overseas,” said Choi, who now runs his own baseball training facility, Choi’s Elite Baseball Academy, in Incheon, west of Seoul. “Perhaps pro teams here lose a chance to draft them, but when they come home, they can apply whatever they’ve learned to Korean baseball and help develop the game further.”

One current major league scout, requesting anonymity, said high school prospects shouldn’t be penalized or criticized for simply making career choices.

The scout, who has also played some minor league ball, said staying put in South Korea doesn’t assure players a success in the KBO, and it makes trying for a big league opportunity in the United States worth a shot.

“Basically, it comes down to wanting to get paid more money to train and play in a better environment,” the scout said. “Making it to the KBO here is no less difficult and challenging. There’s no guarantee that high school prospects will all thrive in the KBO. There are obvious risks on both sides (South Korea and the United States). But I’ve not heard one player say he regretted going to the U.S. minors. They all say they’d do it all over again if given another chance.”

Choi, who signed a minor league deal with the Orioles in 2012 at 28 after stints in Mexico and the U.S. independent ball, said he feels the younger the player when he signs his first overseas contract, the better it is for his development.

And those impressionable teenagers must brace themselves before making the leap, he added.

“I think players have failed in the minors because they weren’t properly prepared,” he said. “You can’t learn anything valuable unless you know what you want to learn. It’s the same with professionals. Before they become free agents or eligible for posting, they have to prepare themselves for years.”

Choi also urged skeptics to step back and try to appreciate just how difficult it is for high school players just to reach the minors.

“Only 0.5 percent of high school players in the United States get to experience professional baseball,” Choi said, citing statistics released by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). “And for South Korean high school players to be good enough to play in the minors is tremendous. I hope people understand how much of an honor that is.”