- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

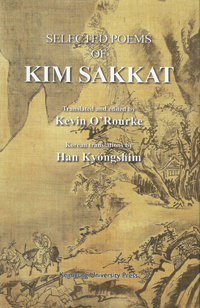

Famous Joseon poet’s work translated into English

By Robert Neff

Selected Poems of Kim Sakkat is, as the title suggests, a collection of poetry from Kim Pyong-yon (1807-1863), better known as Kim Sakkat or the Rainhat Poet. Kim wrote satirical pieces in which he denounced not only the social elite but those around him and has been described as “Korea’s best known and best loved folk figure. ” Yet, despite his popularity, a lot of what we know about him may not be true.

According to Kevin O’Rourke:

“There is an enormous amount of anecdotal material linked to him, very little of it corroborated. There are stories of sexual encounters; tales of liaisons with kisaeng, an account of a putative marriage with an epileptic girl; reports of fiery exchanges with greedy yangban landowners, stingy sodang teaches, and inhospitable teachers, and inhospitable monks; and anecdotes of interaction with people in trouble whom he invariably liked to help. It is difficult to say how much is myth and how much is fact.”

We do know that he lived during a very turbulent period of Joseon Korea an era in which three ineffective boy-kings (Sunjo, Heonjong and Cheoljong) ruled the country. His family had fallen into disgrace through the actions, or rather, the inactions, of his grandfather, Kim Ik-sun (executed in 1812). Considering capital crimes often led to the execution of the entire family, Kim Sakkat was rather lucky to be alive having been smuggled away.

He was an intelligent young man and aspired to do much but he could not escape his family’s past and he eventually became a traveling poet and lived “a life of pent-up resentment.”

He dressed shabbily hemp clothing with straw shoes was apparently impartial to bathing, fond of food and drink, and behaved in an eccentric way. His appearance and past should have made him a pariah of society but instead he enjoyed a great degree of popularity. People invited him to their homes and entertained him with food and drink and in return he would beguile them with his poetry.

But not everyone entertained him so well and not all enjoyed his poetry.

One of my favorite anecdotes is the method in which the poet exacted his revenge upon an inhospitable host. Kim, spying a blank signboard outside of his host’s home, wrote in literary Chinese “The Hall of Precious Delight” (kwi-nak-tang) which greatly pleased his host. It was only after Kim was gone that someone noticed that when read backwards and in Korean it meant donkey or ass (tang-nak-kwi).

O’Rourke’s collection of Kim’s poetry includes those dealing with love, self-reflection, satires and situations and things that the contemporary Korean during the Joseon era would have encountered and been familiar with including fleas, lice, chamber pots, and animals. Many of these poems are outright vulgar yet entertaining.

Kim’s colorful description of the mundane chamber pot is one of my favorite poems. The chamber pot was, according to him, both a neighbor and a friend to a sleeping man. It could be utilized by a lovely lady merely by lifting her skirt and sitting upon its coppery surface while a tipsy man had to “slide piously to his knees. ” O’Rourke’s translation of the title as Piss Pot rather than Chamber Pot is probably more accurate considering Kim’s penchant for vulgarity.

For many of us, poetry is difficult to understand even when it is written in our native language but Kim’s poetry is made even more difficult because it is written in literary Chinese with Korean pronunciation. Each poem in the book is given in its original literary Chinese and then translated in Korean and English but it is O’Rourke’s personal notes that really bring the magic out in the poetry.

O’Rourke acknowledges that “trying to convey in English the skill and sensibility of Kim Sakkat [was] an enormous challenge” and that many around him said that it could not be done.

Was he successful? I don’t know enough about Korean poetry to judge the accuracy of his translations but I do know that he awoke in me a desire to learn more about Kim Sakkat whom Prof. Charles Montgomery of Korea Literature in Translation (ktlit. com) describes as Korea’s and the world’s first battle rapper. The introduction of the book also provides an introduction to Hanshi: Korean poems in Chinese and a fairly comprehensive write up of the sources and previous works published about Kim Sakkat.

I would highly recommend this book to anyone with an interest in Korean studies or, as Montgomery points out, the history of rap music.

Robert Neff is a columnist for The Korea Times.