- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

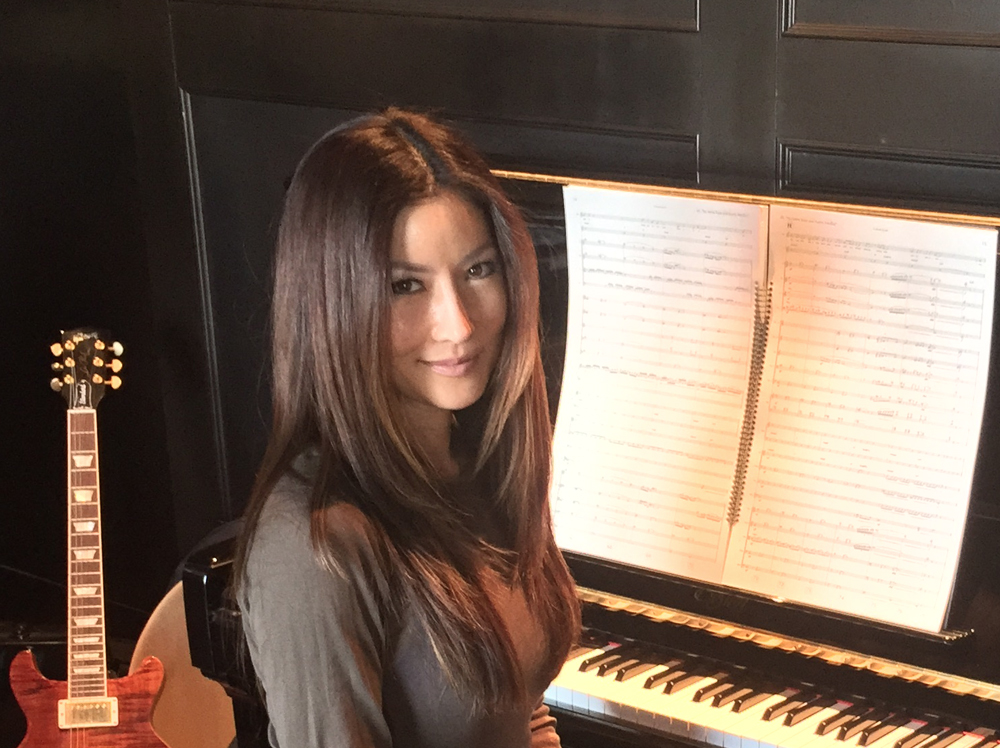

Hollywood music director Sujin Nam looks beyond her own success

By Tae Hong

Sujin Nam was three and a half years old when her mother, a piano teacher, claimed her a musical genius.

The future Hollywood music director, composer and orchestrator had climbed up onto a piano chair on which one of her mother’s students had been playing a piece just minutes before.

“[My mother] heard this music from her studio, the piece she was teaching to a kid that day. So she thought the student hadn’t left,” Nam said. “She went into the studio and found me.”

She had her first piano lesson that day.

Decades later, Nam, 46, has got more than a handful of projects under her name, both American and Korean. And she’s got a new goal: to mentor young musicians looking to do what she does.

In her younger years, jazz was life. Her obsession with the genre — which had only scraped the surface of South Korea’s mainstream by the ’90s — led her to clubs like All That Jazz in Seoul’s Itaewon district, then one of the only places in the city to hear professional jazz.

Can you make me a cassette tape of this music here? I’d like to listen to it, but I cannot find it anywhere. No licensed CDs available, she’d beg the owner.

“I would listen to it over and over until the cassettes got destroyed,” Nam said. “I was going to the club all the time just to listen to music. People drank beer, there were guys all around, but I was not interested in any of that. I went for the music.”

Jazz hunger insatiable, and unknowningly living in a country at the precipice of a pop culture explosion, Nam eventually gave up on both materials she’d ordered from America and inept teachings of private after-school teachers to take the suggestion of a friend attending Manhattan School of Music.

“He said, why don’t you come to New York?” she said. “You want to study jazz, you want to learn jazz, you have to be in New York. There is no other choice.”

Her destination was Mannes College The New School for Music. Then it was the University of North Texas, where genre became a blurred line to Nam while she was a graduate student studying at its acclaimed jazz program.

Her professors and classmates bristled as she played, learned and created a combination of classical and jazz, but it was all just music to Nam, who thought their questions were silly.

“When people say, what kind of musician are you? What kind of composer are you? I jokingly say, ‘Good music. It doesn’t matter what genre that is,’” she said.

Once, she hesitated when her classical composition teacher asked about her favorite composer. Her answer wasn’t the name of a classical great but that of John Williams, the film composer who graced movies like “Jaws,” the “Star Wars” series, “Jurassic Park” and “Harry Potter” with iconic scores. To Nam, the scores were stories of their own.

So it was film music she brought to the table for her final orchestral piece at North Texas, in the midst of her classmates’ big, serious orchestra pieces.

Her move to Los Angeles was inevitable. She drove there alone in a U-Haul truck. She had no college acceptance letter in her pocket or even a waiting job. but the city called for her. The films, the opportunities, the learning curve — it was all there.

“I was so sure that [moving to Los Angeles] was what I was supposed to do,” she said. “I wanted to do this.”

By 1998, she had graduated from the University of Southern California after studying film scoring, ready to take on Hollywood.

She got there eventually, with “Entrapment” later that year, a result of joining hands with Christopher Young, a prolific film music composer and USC instructor.

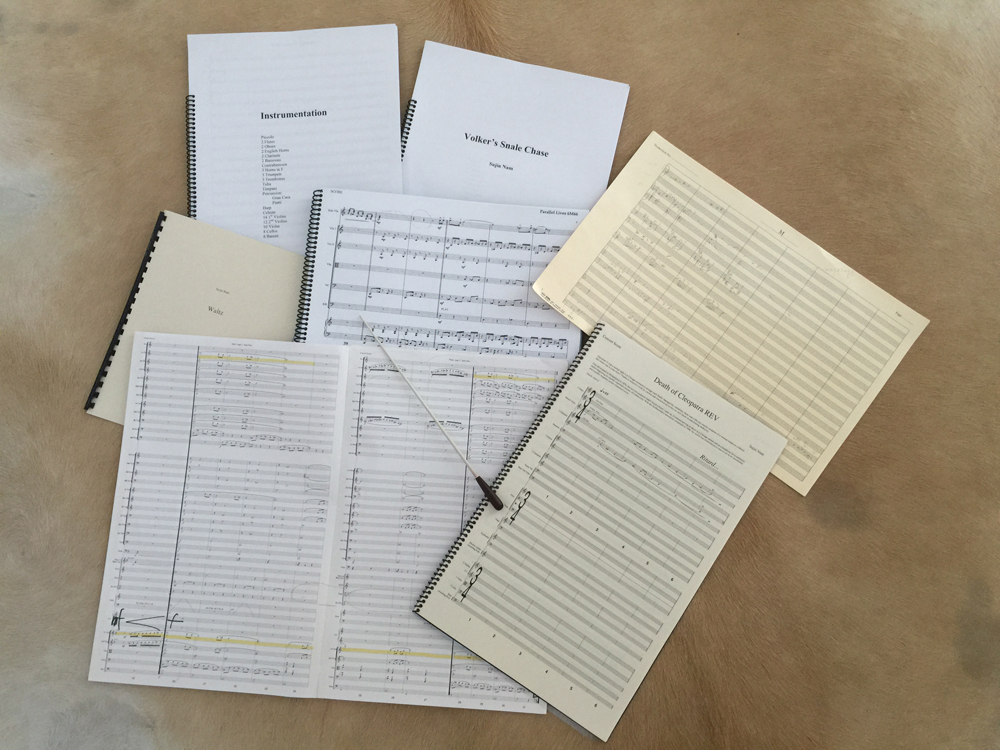

Her projects as music composer, director and orchestrator have now spanned two decades. She’s lent her craft to a handful of films, among them the second and third “Spider-Man,” “Priest,” “Ghost Rider,” “Shanghai Calling,” “The Grudge” and, most recently, the controversial Seth Rogen- and James Franco-helmed “The Interview.”

When Nam works, nothing else gets done. No grocery shopping. No mail checks. No fresh laundry.

No family time.

“I was a workaholic. I still am. But I learned how to take a break. It takes practice. Otherwise, you don’t rest and you just keep going. That’s very easy for me. I was working all the time,” she said.

With her parents back in Korea, it was impossible for Nam to see them. Unless, she thought, she could do a Korean project and be able to work while spending more time with her parents and siblings.

Word that a Hollywood film music director was looking to take on Korean projects didn’t take long to spread. Soon, a bevy of proposals had landed in her inbox.

SBS television drama”Bad Guy” came in 2010, followed by film “Parallel Life” the year after and “Mr. Go” in 2013.

Although recordings were completed in the U.S. with Nam’s usual orchestra, the projects gave her a chance to spend more time in Korea, away from her Hollywood Hills studio.

For the past two years, she and her partner have hosted a musical concert of sorts at their home in lieu of her birthday celebration.

A fine Steinway & Sons piano, the so-claimed runner-up to the one currently in residence at Walt Disney Concert Hall, sits inside the Los Angeles home of film music director and pianist Su-jin Nam.

“It’s a really amazing piano that needs to be played, like how an amazing car or an amazing horse needs to run,” Nam said.

And it is played — every August for the past two years now, during a celebration of music and fledgling musicians held in lieu of Nam’s birthday party. It’s a way for the film music veteran — now also a mentor — to give young talents a chance to network and, hopefully, get their feet in through the oft-glamorous but tough-to-enter doors of Hollywood.

In her days as a young composer, Nam would knock on doors to ask for help. In a constant battle of submitting demos, she’d narrowly miss projects because of a lack of connections.

“The music supervisors would tell me, ‘Su-jin, I personally liked your music better, but the director is a friend of the other composer.’ I could not do anything about that. At first it was disappointing, but now I accept that as, it’s just life,” she said. “You have to have talent, you should absolutely be on top of your craft, that goes without saying. But if you don’t get chosen, and it’s not because of your talent, you have to accept that. I decided to accept that as talent as well.”

The house concerts were her own way of helping out young musicians and composers who need guidance. She would invite visual effects supervisors, film directors and producers, music folks. Last year, the concert had nine different musical groups ranging from contemporary pop to gypsy jazz. It was important to Nam that young musicians without connections may be able to find a way through performing in her home.

As for Nam, there’s always music to be played, to be written and to be directed.

She keeps one thought with her: Be yourself.

“I want to play as a musician and as a composer without thinking what genre I should write or what political standpoint I should take,” she said. “Without thinking, should I keep this [business] relationship? Should I kiss ass? That’s not what I want to do.”

When she visits Korea nowadays, her feet occasionally take her back to All That Jazz, still home to trumpets and saxphones and pianos.

Nam was a fledgling jazz lover, a classically trained pianist, when she left decades ago.

“When I go back to that place, it’s a good memory,” she said. “I have no regret. I worked hard.”