- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

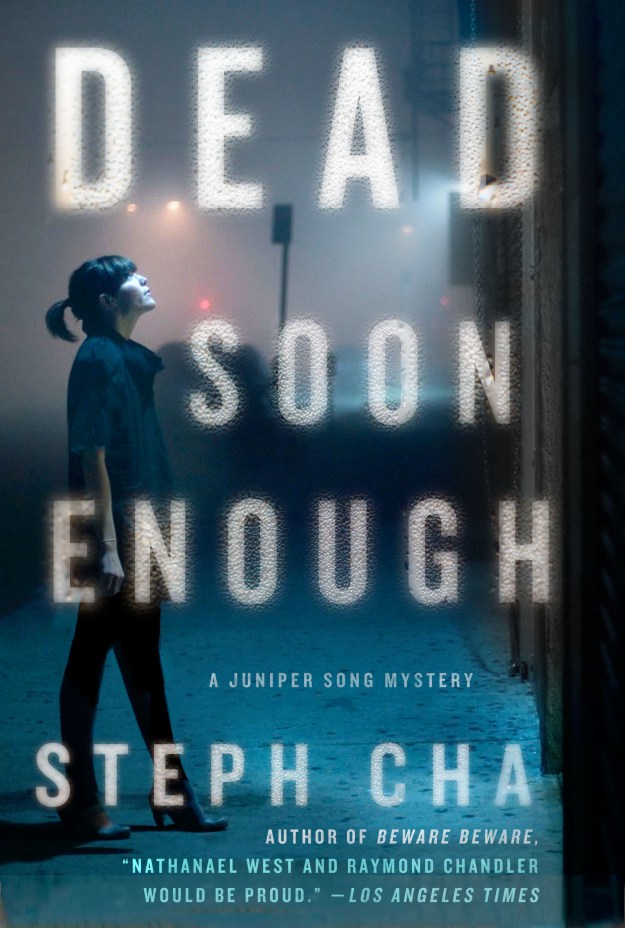

Introducing literature’s only writer of Korean American feminist noir

By Tae Hong

Steph Cha is a daughter of Los Angeles and a daughter of South Korean immigrants.

That she is now a writer of L.A. noir — yes, in the fabric of Raymond Chandler, but also in the way of what she describes as Korean American feminist noir, complete with a young, sharp-tongued detective named Juniper Song in the driver’s seat — well, it just makes sense.

Juniper Song, her private eye, came back in August for a third installment in “Dead Soon Enough,” in which she finds herself in the middle of a community’s longstanding controversy over the Armenian genocide as she helps her new client’s surrogate mother find a missing friend.

In some ways, Song is a reflection of Cha. The author is no private eye, but like her heroine she’s a Yale graduate who, after leaving school, realized a typical office job — in Cha’s case, as a lawyer — was not a good fit.

The sleuth may begin the episode becoming acquainted with the suffocating oversight of a new client bent on keeping a surrogate mother safe during pregnancy, but she’s soon breaking into homes, finding a new love interest in a charming attorney and crashing strip clubs in a quest to uncover the mystery buried beneath an ethnic community’s fight over historical truth and a secret affair.

“I wanted to write a Korean American novel that represented my experience,” Cha said. “It was American, but there were subtle differences in the household I grew up in, where we ate, where we went. The way that Koreans think and talk about each other. I knew that if I wrote a novel from the point of view of a Korean American woman, all of that would naturally get incorporated, just like it is in my life. I didn’t want to exoticize anything; she goes to Koreatown bars because I’ve been there. She went to an Ivy League school because of pressure from her parents. That’s all stuff I know about and that my friends know about. It borrows heavily from my own life and the lives of my Korean American friends.”

Cha’s own story is that of a second-generationer who grew up in Encino but who spent — and spends — pockets of time in K-Town, where she would visit shopping plazas with her mother, eat at an assortment of restaurants (this would come in handy later, as she’s now a prolific Yelper) and enjoy the neighborhood’s nightlife (Gaam, a local mainstay, makes an appearance in the second Song novel. Not to mention, Cha once took the prominent writer Chang Rae Lee, who was visiting town, to Dan Sung Sa, a beloved old-school dive bar).

“[Koreatown] is an interesting place. I mean, there’s a Jewish synagogue in the middle of Wilshire, and right next to that is the Line Hotel,” she said. “It’s layers and layers of stuff. And no one writes about it.”

The neighborhood is home to the private detective firm that employs Juniper and makes frequent appearances in the series.

But when it comes down to it, the novels aren’t K-Town-centric. They’re flesh-and-blood Los Angeles, and it shows — Song’s investigation takes her from Glendale to Downtown to the iconic Langer’s, where the deli’s famous hot pastrami makes an appearance. The City of Angels has drawn generations of writers to write about its rich diversity of neighborhoods, of its glitz and glamour next to grime and dirt, of its racial and class tensions, of the dreams it offers and the dreams it crushes. Cha’s only happy to join them.

“You can choose a different part of L.A. to write about and you’ll never exhaust the source material,” she said. “It’s endlessly interesting. I’ve lived here all of 30 years and I’m still finding new neighborhoods all the time.”

As a newcomer to the literary scene, Cha found relatively quick luck in finding a publisher for her first-ever novel, “Follow Her Home,” the first Juniper Song book released just two years ago. She was 27 years old at the time and still working in law part-time. The second in the series, “Beware Beware,” dropped the following year. “I wasn’t a struggling novelist for many years,” she laughed. “I didn’t wait around for extreme parental disappointment to settle in.”

Her mother — who Cha says is now happy to brag about her daughter’s work — was her first introduction to writing. Cha was maybe five or six years old when she was put through story-writing exercises to learn new vocabulary by her mother. In sixth grade, she went through an Edgar Allan Poe phase and wrote horror fiction she says she never quite finished. It wasn’t until after college that she made her first attempt at long fiction writing.

Through Song, she writes about a similarity between the denial of the Armenian genocide and the denial of the comfort women taken by the Japanese imperial army during World War II, a sensitive subject among Koreans who continue to push for a formal apology from Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

“I get it, by the way. The historical anger,” the private eye tells Lusig, her pregnant, Armenian American friend, during a conversation about cultural sensitivity surrounding the genocide in the novel. As it turns out, the detective’s grand aunt was a comfort woman. “I’ve never lived in Korea. Spent two weeks there total, probably. No one there would see me as anything but American. That said, I know what it’s like to feel rage in my blood.”

Cha’s inclusion of the comfort women stemmed from her own anger.

“It really struck a nerve,” she said. “There were a lot of similarities [with the genocide] in terms of having this discomfort with a heritage issue and what that means for people.”

Heritage and a community’s hurt very much take center stage in Cha’s next novel, now in-progress, which focuses on the historic April 29 riots and Soon Ja-du, a Korean shopkeeper whose killing of a 15-year-old South Los Angeles teen, Latasha Harlins, put irreversible strain on tensions between the black and Korean communities.

“Nobody writes about it from the Korean American perspective,” she said.

At the same time, Cha is adamant that she not write fiction with an intent on forcing certain portrayals of Korean Americans.

“I don’t think I have this responsibility to the world to do that. My mom has told me that she’s apprehensive. She told me, ‘Don’t make Korean Americans look bad.’ That’s not the goal, ever. The goal is to have a balanced portrayal,” she said. “I’m just one artist at the end of the day. I do want to do it well. I want to perform as well and truthfully and powerfully as possible.”

Between the new novel, a screenwriting project and logging book reviews as a contributor for the Los Angeles Times, Cha’s not ready for a fourth Juniper story just yet.

“I can always go back to her. She’s an open-ended character. Sometimes there’s a story that’s best told through a private eye character,” she said. “I feel like I’ve grown up as a writer while writing her, and now I want to grow.”

Pingback: Korean Restaurant In Chandler | Top Greek Restaurants info