- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Is it safe to eat fish?

By Yoon Ja-young

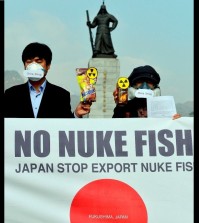

Fish is disappearing as a dinner choice from tables in homes amid growing concern over radioactive waste leaking into the sea from the Fukushima nuclear plant, hit by a tsunami two and half years ago. Despite a government ban on fish imports from Fukushima and seven adjacent prefectures and the monitoring of radiation, fishmongers and seafood restaurants continue to suffer losses. Consumers also find it hard to do without fish — we need protein, and it’s unhealthy to only eat meat day after day.

The Korea Science Journalists Association hosted a forum last week, at which experts engaged in a heated discussion over the issue of radiation leaks and the edibility of fish. Scientists and the government said that people are being needlessly concerned, while NGOs continue to criticize the government regarding curtailing risk to citizens.

Prof. Kim Eun-hee who teaches nuclear engineering at Seoul National University admitted that the ocean is contaminated, as well as the fish there. However, when considering the amount of fish consumed and other factors, the risk isn’t as big as people believe, she pointed out.

“The Ministry of Food and Drug Safety is monitoring contamination of seafood. According to data during the past eight months, contamination was detected only a few times. Even those detected were at less than 10 Becquerel per kilogram (Bq/kg),” she said.

What is a Becquerel? What are millisieverts?

The government lowered the acceptable level of Cesium in seafood to up to 100 Bq/kg, from 370 Bq/kg. A Becquerel refers to the number of nuclear decays per second. Consuming food contaminated with 100 Bq/kg thus means there will be 100 nuclear decays per second within our body if we consume 1 kilogram of it.

Exposure to radiation is measured in millisieverts (mSv). When you eat 10 kilograms of fish contaminated as 100 Bq/kg, for instance, the exposure to radiation will be 0.013 mSv. The government says this is okay, citing academic data. The risk of developing cancer is found to increase when exposure reaches to 100 mSv. When exposed to 100 mSv, five among 1,000 people will develop cancer. The correlation between cancer and radiation hasn’t been proven in terms of lower doses.

However, it doesn’t mean that your safety is guaranteed.

“The government isn’t determining that it is safe at this level (and unsafe at others). The standard is set just for management purposes, but it is set from scientific grounding … It is best not to be exposed to radiation, but in an environment which isn’t 100 percent clean, we have to acknowledge a level of radiation that people can tolerate,” Prof. Kim said.

She said it seems that people are being too particular about radiation. “When you compare radiation risk to other risks, you will understand whether the government’s management is rational or irrational.” She also pointed out that we are being exposed to radiation in our daily lives, through flight, medical equipment and even the Earth’s crust.

Dr. Chin Young-woo, a director at the state-run Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, also thinks consumers are overreacting. “For instance, when you say fish is risky, then would it be less risky if you changed your protein source to meat? Koreans generally barbecue meat. In fact, this can increase the risk of cancer even more. Radiation is only one of the many risk factors.”

Yang Lee Won-young, director of the Korea Federation for Environmental Movements, however, has a different view. She pointed out why consumers must be concerned despite all the scientific data provided by the government. “What is fearful is that we don’t know who will be the victim of radiation. Say the number of cancer patients increased by one in 10,000 people. That could include me and my kids.”

“Radiation is carcinogenic. It is best to have none of it, and you should avoid it if you can … In case of other carcinogens such as Malachite green, food containing it is banned from the market if it is detected. Why should radioactive material of any sort be given any special favors?” she asked. Yang insisted there should be more monitoring around the Pacific, not only of fish from Japan.

To sum up, the ocean is contaminated after the accident in Fukushima, and there is a possibility of being exposed to radiation while eating fish, though the chances are extremely small. If people know that the fish is contaminated with radioactive material, though at very low and “safe” doses, will they willingly eat it? Totally banning imports of Japanese fish may reduce some fears among consumers, but questions remain for all of us, including the government.