- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

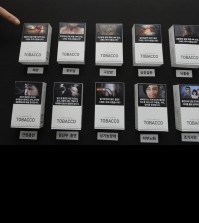

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Korean-American poet shares life story

By Baek Byung-yeul

As many first-generation immigrants will attest, assimilating into a new culture is fraught with challenges ranging from communication problems to homesickness.

For Korean-American Choi Yearn-hong, poetry has always been the best way to forget such hardships.

Choi, founding president of the Korean-American Poets’ Group, says he will never stop writing because, “Poetry is the best way for improving intercultural communication.

“I hope readers can discover the mindset of Korean immigrants through my poetry. I am confident that poetry can help me communicate with readers across generations, national boundaries and racial barriers,” said the 73-year-old in a telephone interview.

Currently residing in a suburb of Washington D.C., Choi began writing in 1963, when he was still in Korea. That year, he made his debut in Hyundae Munhak, the longest-running monthly literary magazine.

Five years later, he departed for the United States to pursue a doctorate in political science at Indiana University, and has lived in the West ever since.

Choi stressed that he never gave up writing despite a busy life in which he served as a professor at several American universities, a columnist for The Korea Times and an assistant for environmental quality of the U.S. Defense Department.

“In the early days as an immigrant, poverty and the language barrier were the highest hurdles,” he said. “But I could withstand the situation by writing poetry.

“Also, I suffered from racial discrimination while teaching at university due to my peculiar accent. But luckily, it all worked out for the best as I have always stuck with poetry,” Choi added.

He said now he feels comfortable with the identity of being “legally American and culturally Korean.”

Choi recently published an anthology, compiling works of 12 Korean-American poets in an effort to promote the works of immigrant writers. Titled, “I Am Homeland,” the book contains 120 poems about the lives of immigrants.

“Many young Korean-American people do not know how their first-generation elders have lived. I am hoping that this anthology can help us understand one another,” Choi said.