- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

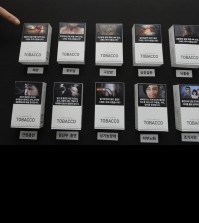

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

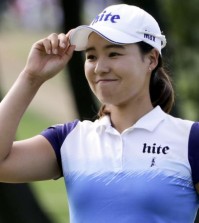

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Newly freed man fights appeal in daughter’s ’89 fire death

In this July 1, 2015, photo, Han Tak Lee, who spent 24 years in prison before a judge threw out his arson-murder conviction, speaks during an interview in the Queens borough of New York. Lee says the 1989 fire that killed his daughter at a cabin in Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains was accidental. Prosecutors want a federal appeals court to reinstate Lee’s conviction and life sentence, insisting he set the deadly blaze. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

NEW YORK (AP) — He lost his daughter in a fire. Then he lost his freedom.

Han Tak Lee spent 24 years in prison before a judge threw out his arson-murder conviction, ruling the highly technical case against him was based on “superstition,” not science.

“I lost all my dreams,” Lee says now, a year after his release from a Pennsylvania prison.

His 1990 conviction was one of dozens to be called into question around the U.S. amid revolutionary changes in investigators’ understanding of arson.

Lee, who emigrated from South Korea with his wife and daughters and earned U.S. citizenship, insists he’s not bitter toward his adopted country — even as he awaits an appeals court ruling that could put him back behind bars.

Prosecutors are urging the Philadelphia-based 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals to reinstate Lee’s conviction and life sentence, insisting he set the fire that killed his mentally ill daughter at a cabin in the Pocono Mountains, about 80 miles west of New York. Lee has always maintained the fire was accidental.

“I love America and I expect America to make the right decision,” Lee, speaking Korean, told The Associated Press in a recent interview at his Queens apartment, where he prominently displays his framed Certificate of Naturalization.

“I feel that justice is still alive,” the 80-year-old former clothing store owner said. “That’s what I want to make clear.”

Lee’s case illustrated the gap between what fire investigators thought they knew about arson and the reality of it.

Combing through the wreckage of the Lees’ cabin, investigators quickly suspected foul play. They found eight or nine burn patterns, irregular fractures in the window glass, and deeply charred and blistered wood — all evidence that an accelerant had been used to set the fire, according to the orthodoxies of the day.

And that’s what prosecution experts told the jury at Lee’s trial.

But fire researchers, in the meantime, had been putting these entrenched beliefs about arson to the test — and found them lacking any scientific merit.

In 1992, the National Fire Protection Association published a guidebook for fire investigations, called NFPA 921, that addressed misconceptions about arson and provided a roadmap for determining a fire’s origin and cause. It is still considered the gold standard for arson probes.

“It’s definitely improved the skills of arson investigators, leading to better arson investigations,” said the NFPA’s Ken Willette.

But NFPA 921 came too late for Lee, who had already been convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Brother-in-law John Yun said no one in the family blamed Lee for the death of 20-year-old Ji Yun Lee.

“Never, never,” he said. “This is a 100 percent innocent person.”

Prison was a lonely place for Lee, whose English is limited. About the only time he got to hear his native tongue was during quarterly visits from his sister and her husband.

“I immigrated to a good country and I ended up like this. It’s unbelievable,” he said.

After years of appeals, the 3rd Circuit granted Lee’s request for an independent review of the evidence. The review, led by a magistrate judge, concluded the expert testimony used to convict him was based on “little more than superstition.”

Prosecutors say the discredited testimony constituted “harmless error” in light of other “overwhelming” evidence in the case. U.S. Magistrate Judge Martin Carlson disagreed, saying in last year’s ruling that the prosecution’s case, without its scientific underpinning, rested on “thin reeds.” Another judge agreed and ordered his release.

Lee, whose wife divorced him while he was in prison, has been trying to rebuild his life since getting out in August 2014. He’s learned to work a cellphone, watches Korean television on a flat-screen TV, and jogs each morning. He met his two grandchildren for the first time.

Though he says he still believes in the U.S., he has no love for Monroe County District Attorney David Christine, who prosecuted Lee in 1990 and whose office filed the appeal.

“The prosecutor is a bad person,” Lee said. “He persecuted a good person. He kept hurting me over and over, not just once or twice, but over and over.”

Christine did not respond to requests for comment on the case.

The 3rd Circuit held oral arguments in June. It’s not clear when the court will rule.

Lee said he’s not afraid he’ll be put back in prison “because I’m not guilty.”

He won’t even entertain the thought.

“I don’t want to think about it,” Lee said. “I don’t want to go back.”