- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

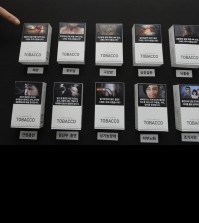

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

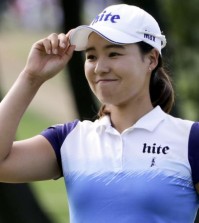

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

[NY Times] Lonely end for S. Koreans who can’t afford to live, or die

SEOUL, South Korea — In a culture in which funerals are often lavish three-day affairs with hundreds of guests, the recent funeral for Song In-sik was modest at best. It had only one guest — an activist who volunteered to hold a ritual for a person he had never met.

The activist, Park Jin-ok, placed a table of fruit, dried fish and artificial flowers before the refrigerated unit that held Mr. Song’s remains in the morgue of Sungae Hospital in Seoul. He burned incense and bowed, before the impatient mortuary director asked him to pack up and leave.

Mr. Song, 47, died in July; his body was found three days after his death, decomposing in his rented room. He was lucky to get even a makeshift funeral. A growing number of South Koreans are dying alone, with no relative willing to claim their remains and perform a ritual Koreans believe is essential to easing the deceased’s passage to the other world.

The surge in so-called lonely deaths — to 1,008 last year from 682 in 2011, according to government statistics — provides a small but poignant glimpse of how South Korea’s long-cherished traditional family structure is changing. Though South Koreans have mostly benefited from a strong economy in recent decades, families have come under strain from economic and demographic upheaval.