- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

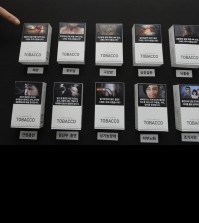

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

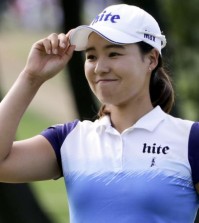

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Q&A: Koreas to resume emotional reunions of divided families

In this Oct. 15, 2015 photo, South Korean Kim Wu-jong, 87, who will travel to North Korea to meet his younger sister, looks at a document from the Red Cross during the interview at his home in Seoul, South Korea. Kim and about 640 other South Koreans will meet their North Korean relatives at the authoritarian country’s scenic Diamond Mountain resort in a reunion program that begins Tuesday, Oct. 20. Tens of thousands of people on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone desperately seek such reunions, but the two countries have pulled off relatively few of them. (AP Photo/Lee Jin-man)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — Kim Wu-jong is partially paralyzed, poor and lives alone in a small, run-down home in Seoul. But the 87-year-old feels like the luckiest man in South Korea: This week he will travel to North Korea to meet his younger sister, the “flower and princess of my family,” for the first time since the Korean War pulled them apart more than six decades ago.

“I cannot describe how happy I am,” Kim said in a recent interview at his home, with a broad smile. “It’s better than winning the lottery.”

Kim and about 640 other South Koreans will meet their North Korean relatives at the authoritarian country’s scenic Diamond Mountain resort in a reunion program that begins Tuesday. Hundreds of thousands of people on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone want such reunions, but the two countries have pulled off relatively few of them.

Here are five questions and answers about the meetings:

—

HOW DID THE BITTER RIVALS AGREE TO THE REUNIONS?

This round, the first since February 2014, was agreed to in August, after the Koreas met for marathon talks to defuse a standoff that had them trading fire and threatening war. Anger had risen after Seoul blamed Pyongyang for land mine blasts that maimed two South Korean soldiers.

The loathing the Koreas feel for each other has made at least one round of previous reunions fall apart at the last minute. But these reunions, set to run until Oct. 26, look secure because North Korea hasn’t followed through on hints that it would conduct a satellite launch. That would have jeopardized the reunions and deepened animosities in the region because the U.S., South Korea and their allies regard such launches as banned tests of long-range missile technology.

—

WHAT MAKES THE REUNIONS SO EMOTIONAL?

The millions of people completely separated during the turmoil of the 1950-53 war are banned from crossing the world’s most heavily armed border, across which hundreds of thousands of combat-ready troops still face each other. The rivals have yet to establish a peace treaty to replace their fragile 1953 armistice, which means the peninsula is still technically in a state of war.

Both Koreas prohibit their citizens from exchanging letters, phone calls and emails with people in the other country without government permission. Most people who apply for reunions are in their 70s or older and long to see their loved ones before they die.

At each of the past reunions, television cameras crowded around weeping family members during their few days together. They embraced each other and asked for details about their lives and other loved ones.

This week’s reunions take place in two waves. The first runs Tuesday through Thursday; Kim is part of the second group, meeting Saturday through Monday.

His 81-year-old sister, Kim Jong Hui, is his only direct family member still living and the only girl among six siblings. “My brothers and I took turns taking her to kindergarten because we worried about boys harassing her,” Kim said with a laugh.

When they meet again, he knows he’ll weep.

“I’ll tell her that we should live as long as we can so that we can see each other again,” he said.

That could be a long time indeed. No Korean has been allowed a second reunion.

—

WHO CAN ATTEND?

In each reunion, up to 100 elderly people from each side usually meet their relatives. The numbers are boosted because many are accompanied by their children and other family members.

South Korea uses a computerized lottery system, while North Korea reportedly chooses citizens seen as most loyal. Nearly half of the 130,410 South Koreans who have applied to attend a reunion have died.

Ten of the 100 South Koreans initially given a chance to attend this month’s reunions decided not to go because they were sick or had learned their close relatives had died, according to Seoul’s Red Cross.

Park Bok-nam, 70, is going to North Korea to meet distant relatives even though she has been told that her mother and three brothers died.

“I wonder whether they will be able to tell me how my mother lived her life,” Park said in a telephone conversation, sobbing. “I can’t remember her well anymore.”

—

HOW WERE FAMILIES SEPARATED?

Each person has a different story about their separation from loved ones during the chaos of war. What they have in common is shock that their homeland remains so bitterly split.

Kim said he didn’t take any family photos with him when he fled to South Korea several months after North Korea invaded the South in June 1950. He thought he would soon return. “It never crossed my mind it would be this long,” he said.

Choi Hyeong-jin, 95, said he still feels guilty for leaving behind his wife and two daughters in their home in the North’s northeastern Hamgyong province when he came to South Korea in early 1951. He said he made the excruciating decision not to bring them because it was so cold he thought they might not survive the trip.

Choi is to reunite this week with his youngest daughter, who was 2 when he left her. She is now 64.

“I am not sure if I will even be able to recognize her. I don’t even remember how she looked as a baby,” Choi said.

—

WHY ARE REUNIONS HELD SO INFREQUENTLY?

There was a one-time, smaller-scale reunion in 1985. But reunions in their current form first started in 2000, part of a slew of major cooperation projects agreed upon after the countries’ leaders held their first-ever inter-Korean summit talks that year.

About 18,800 Koreans have participated in 19 face-to-face reunions and about 3,750 others have been reunited by video.

Seoul has long called for more participants and more regular reunions, but North Korea balks; analysts say Pyongyang worries its citizens will become influenced by the much more affluent South, which could loosen the government’s grip on power. The reunions are also considered a coveted North Korean bargaining chip in negotiations with South Korea.