- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

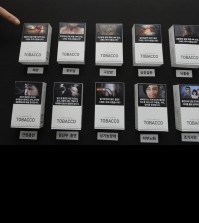

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

South Carolina cleans up, but worries remain amid floods

This aerial photo show flooding around homes in the Carolina Forest community in Horry County, between Conway and Myrtle Beach, S.C. The Carolinas saw sunshine Tuesday after days of inundation, but it could take weeks to recover from being pummeled by a historic rainstorm that caused widespread flooding and multiple deaths. (Janet Blackmon Morgan/The Sun News via AP)

COLUMBIA, S.C. (AP) — The family of Miss South Carolina 1954 found her flood-soaked pageant scrapbook on a dining room floor littered with dead fish on Tuesday, as the first sunny day in nearly two weeks provided a chance to clean up from historic floods.

“I would hate for her to see it like this. She would be crushed,” said Polly Sim, who moved her 80-year-old mother into a nursing home just before the rainstorm turned much of the state into a disaster area.

Owners of inundated homes were keeping close watch on swollen waterways as they pried open swollen doors and tore out soaked carpets. So far, at least 17 people have died in the floods in the Carolinas, some of them drowning after trying to drive through high water.

Sim’s mother, known as Polly Rankin Suber when she competed in the Miss America contest, had lived since 1972 in the unit, where more than 3 feet of muddy water toppled her washing machine and turned the wallboard to mush.

“There’s no way it will be what it was,” said Sim. “My mom was so eccentric, had her own funky style of decorating, there’s no way anyone could duplicate that. Never.”

Tuesday was the first dry day since Sept. 24 in South Carolina’s state capital, where a midnight-to-6 a.m. curfew was in effect. But officials warned that new evacuations could come as the huge mass of water flows toward the sea, threatening dams and displacing residents along the way.

Of particular concern was the Lowcountry, where the Santee, Edisto and other rivers make their way to the sea. Gov. Nikki Haley warned that several rivers were rising and had yet to reach their peaks.

“God smiled on South Carolina because the sun is out. That is a good sign, but … we still have to be cautious,” Haley said Tuesday after taking an aerial tour. “What I saw was disturbing.”

“We are going to be extremely careful. We are watching this minute by minute,” she said.

Georgetown, one of America’s oldest cities, sits on the coast at the confluence of four rivers. The historic downtown flooded over the weekend, and its ordeal wasn’t over yet.

“It was coming in through the kitchen wall, through the bathroom walls, through the bedroom walls, through the living room walls. It was up over the sandbags that we put over the door. And, it just kept rising,” Tom Doran said, bracing himself for the next wave. “If I see a hoard of locusts then I’m taking off.”

In Effingham, east of Columbia, the Lynches River was at nearly 20 feet on Tuesday — five feet above flood stage. Kip Jones paddled a kayak to check on a home he rents out there, and discovered that the family lost pretty much everything they had, with almost 8 feet of standing water in the bedrooms.

“Their stuff is floating all in the house,” Jones said. “Once the water comes in the house you get bacteria and you get mold.”

In downtown Columbia, about 200 workers rushed to fix a breach in a canal that is threatening the city’s water supply to its 375,000 customers. The city’s main intake valve is in the canal, and the water level was steadily dropping, Columbia Utilities Director Joey Jaco said.

Crews planned to work into Wednesday morning, sinking a barge and piling bags of rocks and sand on top to try and block the hole in the canal, Jaco said.

If the water gets below the intake value, there is less than a day’s supply in a reservoir.

“We need to make sure we get this dam constructed very soon to make sure we stay above a minimal level,” Jaco said.

Haley said it was too soon to estimate the damage, which could be “any amount of dollars.” The Republican governor quickly got a federal disaster declaration from President Barack Obama, freeing up money and resources. South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham, a Republican presidential candidate, promised not “to ask for a penny more than we need” and criticized other lawmakers for seeking financing for unrelated projects in disaster bills.

Water distribution was a challenge. In the region around Columbia, as many as 40,000 homes lacked drinking water, and Mayor Steve Benjamin said 375,000 water customers will likely have to boil their water before drinking or cooking for “quite some time.”

The power grid was returning to normal after nearly 30,000 customers lost electricity. Roads and bridges were taking longer to restore: Some 200 engineers were inspecting about 470 spots that remained closed Tuesday, including a 75-mile stretch of Interstate 95.

Some drivers had a hard time accepting the long detours around standing water. In Turbeville, Police Lt. Philip Wilkes stood at a traffic stop, telling motorists where they could go to avoid flooded roads and dangerous bridges.

“Some people take it pretty good,” Wilkes said. “Then you’ve got some of them, they just won’t take no for an answer. We can’t part the waters.”

South Carolina was soaked by what experts at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called a “fire hose” of tropical moisture spun off by Hurricane Joaquin, which mostly missed the East Coast.

Authorities have made hundreds of water rescues since then, lifting people and animals to safety. About 800 people were in two-dozen shelters, but the governor expects that number to rise.

In Columbia, Ray Stilwell told a harrowing story of escaping his home along Gills Creek, where nearly 17 inches fell in as many hours Sunday.

He was upstairs when his backdoor failed and water rushed in, and was nearly swept away as he tried to make it outside to higher ground. He survived by hanging on to a neighbor’s gate, and then climbing atop a patio table.

“I’m so grateful. If you hear me complain, remind me that I’m lucky to be here,” the 59-year-old schoolteacher said. “God allowed me to be here; Now I’ve just got to figure out what to do with the extra time I’ve been given.”

Stilwell took a long look at the nearby creek, which was still raging and foamy but didn’t seem to be rising. A worried neighbor called out, asking what was going on. “Just keep watching the water level right now,” Stilwell responded.

The Black River reached 10 feet above flood stage in Kingstree, breaking a 1973 record by more than 3 feet, according to Town Manager Dan Wells, who found himself involved in a porcine rescue mission Tuesday.

After a wild hog fell into the rushing river and slammed into the town bridge, Wells and a colleague used a stun gun and captured the exhausted hog, trussed its legs with duct tape and pulled it into a pickup truck to be released in a nearby forest.

“It wasn’t on my list of things to do today, I can tell you that,” said Wells.

___

Dalesio reported from Effingham. Contributors include Associated Press writers Bruce Smith in Charleston; Alex Sanz in Georgetown; Susanne M. Schafer and Jeffrey Collins in Columbia; Meg Kinnard in Blythewood; and Seth Borenstein in Washington, D.C.