- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

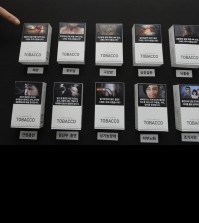

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

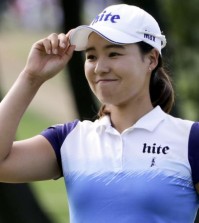

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

Tampon tax: Does being female in the US carry unfair costs?

NEW YORK (AP) — Margo Seibert and Natalie Brasington don’t think women should have to pay a “period tax,” and like a growing number of other women, they are publicly questioning whether being female in the U.S. carries unfair costs.

The pair are among five New York City women who filed a lawsuit last week arguing that it was unconstitutional for the state to levy sales tax on tampons and sanitary napkins while offering medical product exemptions to many other items used by both genders, like lip balm, foot powder and dandruff shampoo.

The case, they say, is about more than the few cents in tax levied on each pack.

Sick of the social taboo, and frustrated by a lack of access for some to a staple, these women and others are talking very publicly about menstruation and gaining political traction that would have been impossible a generation ago.

A national push to abolish sales tax on tampons is gathering steam, led by social media campaigns like #periodswithoutshame. At least six states are now considering legislation.

Cosmopolitan magazine launched an online petition, and even President Barack Obama has questioned why the items are taxed.

“I tend to talk about my period quite a bit, to anyone who will listen,” said Seibert, a 31-year-old actress and founder of an online campaign that promotes a “shame-free” period.

Brasington, a 31-year-old photographer, said the tax affects women disproportionately and is a genuine burden for poorer women.

“Being a woman is so expensive,” she said.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, a vice president at the NYU School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice, said she began writing articles and op-eds on “menstrual equity” when she discovered food pantries were desperate for sanitary napkins and tampons because poor women can’t afford them.

The tax campaign reflects a broader debate over “gender pricing,” or charging women and men different rates for similar products and services, from haircuts to razors to T-shirts.

New York City’s consumer protection agency studied the cost of 800 common household items last year and found that products marketed to women cost, on average, 7 percent more than similar products for men.

“Women’s outcry over this issue isn’t just about the tax on tampons. It’s a reflection of the routine unfairness that seeps into our everyday lives,” said Sonia Ossorio, president of the National Organization for Women in New York. “At the end of the day, the tampon tax movement is one small way to challenge the broader sexism that still persists. Because that’s the real taboo here.”

While women’s advocates have long lamented that many women’s products cost more, their providers say there can be legitimate reasons — a more decorative product or more complicated haircut, for instance. And some have noted that women sometimes pay less: for life and auto insurance, for example.

Nationwide, 40 states tax feminine hygiene products, deeming them non-necessities or even “luxury items,” while making exceptions for products as similar as adult incontinence pads.

Currently, five U.S. states exempt tampons and other feminine hygiene products from their sales tax, which varies around the country from about 2.9 percent to as high as 7.5 percent. Another five states have no sales tax.

New York taxes tampons and sanitary napkins as tools “to control a normal bodily function and to maintain personal cleanliness.”

The 4.5 percent state sales tax on the products costs New York women millions of dollars a year; estimates range from about $7 million to twice that, a minute fraction of the state’s $142 billion budget.

Advocates say the cost, however small it may seem, is burdensome for poor women, who also can’t purchase the products with food stamps.

“Having one’s period is not a luxury,” state Assemblywoman Linda Rosenthal, a Democrat who has proposed abolishing the tax. “Because of our biology, we bear this extra cost, and the state should not compound it.”

The state Department of Taxation and Finance declined to comment, citing the lawsuit. Two major manufacturers of feminine hygiene products, P&G, the maker of the Tampax brand, and Edgewell Personal Care Co., the maker of the Playtex brand, didn’t respond to inquiries this week about the tax issue.

Zoe Salzman, the attorney on the New York case, said they’d push to get a judge to rule the tax unlawful.

“If men had to use these products every month, they would already be tax-exempt,” she said.

Meanwhile, the legislative proposal has yet to get a hearing, though supporters are hopeful about its prospects, especially since Democratic Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently said the tax should be abolished.

That wasn’t the sense in Utah, where a legislative committee last month nixed a proposal to tax-exempt the items. While some members of the all-male committee supported the idea, others questioned where the state would draw the line on what to tax in the future.

The Los Angeles Times, in an editorial last week, expressed similar concerns in opposing a tax exemption that California lawmakers are considering.