- California Assembly OKs highest minimum wage in nation

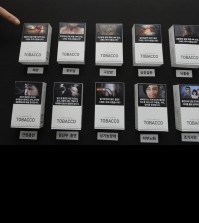

- S. Korea unveils first graphic cigarette warnings

- US joins with South Korea, Japan in bid to deter North Korea

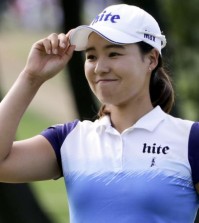

- LPGA golfer Chun In-gee finally back in action

- S. Korea won’t be top seed in final World Cup qualification round

- US men’s soccer misses 2nd straight Olympics

- US back on track in qualifying with 4-0 win over Guatemala

- High-intensity workout injuries spawn cottage industry

- CDC expands range of Zika mosquitoes into parts of Northeast

- Who knew? ‘The Walking Dead’ is helping families connect

With jobs scarce, S. Korean youth fall prey to abuse

By Park Sojung

SEOUL (Yonhap) – Lee Ga-hyeon, a 23-year-old university senior, says she was completely thrown off guard when the manager of a McDonald’s branch where she worked fired her last September.

“You can’t come to work starting tomorrow,” she recalled the manager saying. Lee had considered herself a reliable worker, being on call whenever needed. The manager had even told her he “felt relieved” when she was on the shift, she said.

She surmises her activities with Alba Yeondae, a union for part-time workers, might have been the reason, although McDonald’s maintains it does not discriminate against employees based on political beliefs.

McDonald’s employs about 17,000 part-timers in South Korea, and Lee says many of them lose their jobs or get left off work schedules on the employer’s whim.

According to a survey by Alba Yeondae last month, 54 percent of McDonald’s workers have been told by their bosses to come to work later or leave earlier than scheduled so they could be paid less, a finding that has put the global fast-food giant under public scrutiny here.

A total of 16,250 former and current McDonald’s employees participated in the online survey from Dec. 6-14.

Rebutting the findings, McDonald’s said the survey lacks credibility because it was not done by a professional pollster.

The American food giant says it pays a third-party law firm to scrutinize each branch for possible law violations.

The abuse of young workers, however, hasn’t been isolated to the restaurant industry.

In December, a prominent South Korean fashion designer, Lee Sang-bong, was found to have paid a paltry wage of 100,000 won ($92) to trainees, including overtime pay, a month. Full-time workers earned 1.1 million won a month, still below the minimum wage, according to unionized fashion industry workers.

Designers also commonly hired candidates based on looks so they may double as fitting models without extra costs, according to these workers.

Lee Sang-bong later apologized through a press release, saying he had been “so focused on his life as a designer that he neglected his duties as a business owner.”

Also last month, WeMakePrice, a popular social commerce website, was found to have treated its 11 new hires in a similar manner.

These workers, who were hired on condition of completing a probationary period successfully, were paid 50,000 won a day and were given a full-time workload, they said.

All of them were fired after two weeks because “none of them met the standards,” the company said.

The firm re-hired them after the news sparked controversy.

Experts say a shortage of jobs and tougher business conditions resulting from a prolonged economic slowdown may be to blame.

“First, there aren’t enough good jobs for young people,” said Choi Pae-kun, an economics professor at Konkuk University. “And the people who hire them are struggling themselves.”

Job creation in South Korea hit a 12-year high last year, with more than 500,000 workers being newly employed.

The increase, however, was mostly driven by non-regular employees, whose contracts typically last up to two years, and the self-employed.

Official data show that more workers aged 15-29 were signing up for these non-regular jobs, and those in their 60s and above were opening their own businesses, which, according to Choi, rarely made it past their first year.

“These business owners are barely making ends meet themselves,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean it’s OK to abuse young workers. The government should step up efforts to eradicate these illegal hiring practices.”

Taking a cue from the enraged public, the labor ministry said on Jan. 10 that it will clamp down on businesses that are found to have abused young workers.

Another McDonald’s part-timer, however, said government efforts need to be consistent.

“Ever since McDonald’s got negative press, I’ve seen more labor attorneys stopping by to check out my branch,” she said, only giving her surname Jang for fear of retaliation. “I’ve never seen them before, so who knows if they’re here to stay.”